Remembering and forgetting at the Sixth Floor Museum

Indulge in the prurience of this memorial to Dallas's Worst Day Ever

This is Well, Actually, a “zippily substantive”1 newsletter devoted to history, culture, and internet rabbit holes. If you like it, consider subscribing or forwarding it to a friend. Or both. I’m not going to tell you how to live your life.

(Here is Part I of my Dallas travelogue.)

I. Assassination Vacation

The Sixth Floor Museum, located on the … sixth floor of the former Texas School Book Depository building, commemorates the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963. I am here because I like weird museums; I am also here because I need a break from my brother’s very weird company. I am also here in honor of Richard N. Shine, my late father and a full-bore JFK conspiracy theorist who subscribed to the JFK newsletter The Third Decade—we might think of it as a proud Substack antecedent—and occasionally rendezvoused with other enthusiasts at a local Friendly’s. (I only know this because one time he couldn’t find a babysitter and had to take me with him.) I don’t know whether he ever got to visit the museum, which opened on President’s Day in 1989, but it’s not impossible; it’s more likely that he went to one of the other assassination museums, since closed. (More on that later.) The personal is political, I guess????

I’m skeptical about this enterprise. A couple of years ago, the museum’s CEO told a reporter that “she also wants visitors to understand that the Sixth Floor isn’t stuck in 1963, when he was shot and killed by Lee Harvey Oswald.” (The occasion for this remark was the debut performance of a piece for string quartet commissioned by the museum in honor of its thirtieth year.) And when I read that sentence, I thought, “Oh-ho, I shall be the judge of that, ma’am.”

II. What is this place?

It’s not clear to me that it’s possible to create a classy assassination museum, but it’s also not clear that there was any way to avoid building one. City officials and citizens of Dallas were not eager to commemorate the assassination. This was in part because of overwhelming national hostility toward Dallas, subsequently dubbed “the City of Hate” in the tabloid press. As Mayor R.L. Thornton remarked in December 1963,

I've heard people talking about erecting a monument in their sadness. For my part, I don't want anything to remind me that a president was killed on the streets of Dallas. I want to forget.

They certainly tried to forget: a Mayoral committee emphatically wanted to memorialize Kennedy's life in a way that did not include reflection on, or acknowledgment of, the circumstances of his death, and the city donated land for a new memorial plaza nearby; this was where Philip Johnson’s memorial was later erected. No marker of any kind was laid in Dealey Plaza until 1966, and this only occurred after a local woman who had visited the site more than one hundred times undertook a vigorous grassroots campaign for it.

As for the book depository, their feelings didn’t much matter: the building was privately owned by Texas oilman D. Harold Byrd.2 The book distributor, also privately owned, remained in the warehouse until 1970, when Byrd finally sold the building at auction. A pre-sale brochure noted blandly,

Many excellent uses can be found for it. It was from window of this building, the Warren Commission reported, that shots were fired that killed President John F. Kennedy.

Nashville record producer Aubrey Mayhew bought it. (This story is eccentric characters all the way down, so, briefly: Mayhew owned Little Darlin’ Records. He produced Charlie Parker and worked with Clint Eastwood and co-wrote “Take This Job and Shove It”!!!!3) Mayhew saw one excellent use for the building: a museum for his personal collection of Kennedy memorabilia, which eventually topped 300,000 items. Mayhew also had very poor management skills and lost the building in foreclosure three years later. D. Harold Byrd bought it back; in 1977, the County bought the building and renovated the first five floors for County offices. They planned to just leave the sixth and seventh floors empty.

So, 1977: there’s a plaque in Dealey Plaza, and someone painted an X in the middle of Elm Street to mark the spot where the President was shot (people would run into the street and stand on the X for photos?) and Byrd took down the giant Hertz billboard that sat atop the Book Depository when he reacquired the building. Otherwise, things look the same. Everything looks the same.

III. Ghosts of museums past

But again, people wanted to remember, and they found ways to do it anyway. Dealey Plaza remained, stubbornly, a site of tourism or pilgrimage or both. A decade after the assassination, a Dallas travel guide in The New York Times reported that you could find people wandering around the site and environs at all hours of the day. People were attached to the building, too, and had been almost immediately: the Book Depository "already has become a shrine," a reporter observed on November 26, 1963. "People will journey to it in years to come and stand and stare."4

The Sixth Floor Museum is but one in a succession of assassination museums. Against the wishes of the better classes of Dallasites there have been several unsanctioned collections since Kennedy’s death. One of the most significant—though not the first5—was the JFK Museum, which operated from 1970-1982 out of a storefront one block away from the Book Depository.6 Its highlight was a 22-minute multimedia slide show about the assassination called “The Incredible Hours.”

“Multimedia slideshow” does not really begin to explain it, honestly. What was “The Incredible Hours”©? (Yes, it was copyrighted.) Viewers looked down on two enormous electric scale models, where the events of November 22 played out, the motorcade’s path of travel illuminated by a spotlight, while screens nearby displayed 140 slides, real news audio played on the speakers, and a narrator spoke in dulcet tones. This is some Surround Sound shit, and I doff my cap to the humble local entrepreneurs who built it. There was also an extensive gift shop. ("’All museums have gift shops,” the woman at the counter told an Associated Press reporter in the early 1970s. “Don't be unfair.”)

But there was still a sense that something should be done with the building itself, and as downtown developers threatened encroachment (they forced the Sissoms’ museum to close), the city began to take the prospect seriously.

In 1979, the Dallas County Historical Commission accepted a recommendation from the NEH to turn the sixth floor into a museum,7 but the process of building it took a decade. Lining up support from the city’s important figures, including luxury retail magnate Stanley Marcus and a member of the Dealey family; recovering from multiple arson attempts at the building; raising nearly six million dollars in private and government funding through a period of recession; and battling with downtown developers over parking garages and proposed transit projects all took time. The museum finally opened on President’s Day, 1989. Admission was $4.8 Today, something like a quarter-million people a year visit the Sixth Floor Museum, including me!

IV. Ambient noise

So. What’s it like? The Sixth Floor Museum is a noisy place. There are no floor-to-ceiling walls in the space, just partial dividers, and the design is poor: sound from various sections of the exhibit leaks everywhere. Several short documentary films are narrated, invariably, in rumbling bass tones and layered with archival audio and chattering typewriters and Super 8 cameras running and dark, pulsing, urgent scoring.9 In one spot, the ABC Radio bulletin announcing the assassination plays in a constant loop. Maybe 20 feet away, a kiosk plays a non-narrated film, also on a loop, that pieces together live audio and video from that day, including a press interview with Lee Harvey Oswald. Gunshots ring out and sirens wail from various corners all day long; the President is killed over and over and over again.

V. Looking out The Window

A dramatic highlight, of course, is The Window. You can’t get very close to The Window—it’s behind Plexi-glass in a little tableau where they’ve restaged the sniper’s perch with replicas of the original boxes. You can see the plaza from Oswald’s perspective, just not while you’re at the museum: since 1999, the museum has maintained a webcam, positioned “inside one of the replica boxes in the sniper's perch window,” which are “arranged as they appeared when investigators first arrived on November 22, 1963.”10 Now, I’m not sure that any photos were taken after investigators had already been there several times, so it’s not clear that that is how they looked that day, but I digress.

Or … do I? I subsequently learned that The Window might not even be the actual literal window. (The explanation is … very involved, but) D. Harold Byrd had the window removed—or, at least, a window removed—in early 1964 and displayed it like a trophy in his home. His son donated it to the Sixth Floor Museum in 1994, where it was on display for a dozen years; he attempted to auction it off in 2007.

But wait: there's more. Aubrey Mayhew claimed that Byrd had removed the wrong window in 1964. Mayhew, in turn, had carpenters remove the southeast corner windows, which he thought to be the originals, to keep for himself, and replaced them with the windows from yet another corner of the building. In 1992, the former owner of the Book Depository filed this affidavit affirming this—Byrd took the wrong one; Mayhew took the right one.

So The Window is almost certainly not the window. I don’t know where it is now.

But I’m also not sure most visitors really care about that. The window casing there today has become the real thing by virtue of being all there is.

VI. Elevating conspiracy theories

A significant part of the museum is given over to addressing the conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination, beginning with the doubts raised about the Warren Commission report. This makes sense, because, at this point, there’s no way to talk about the assassination without talking about the conspiracy theories; in one light, it’s all part of a single event with a horizon that stretches across decades.

Questions and suspicion surrounded official accounts of the assassination almost from the very beginning. (I’m trying to stay out of the business of evaluating whether those suspicions were logical; if you’d like to know more about them, you will find … lots of sources.) Initially unknown to one another, the men and women who became known as the “first-generation critics” began collecting and analyzing anything remotely evidentiary right away. We’re talking about people of all backgrounds here (though, as far as I can tell, almost exclusively white people): an Oklahoma housewife hauled her four children to Dallas in February 1964 so she could track down and interview eyewitnesses. Bookkeepers and lawyers and philosophy graduate students and small business owners and epidemiologists deluged the official investigative committee with letters and dropped in on FBI field offices across the country.11 Since then, self-fashioned assassinologists, still a motley crew, have published millions of words about their theories and millions more about their internecine disagreements. (The big questions: Did or did not Oswald act alone? If he didn’t, who else was involved? How many bullets were fired from where at what moments, how many struck the President?)

I was curious, then, about how the museum handles all of this. Do they say anything definitive? No. (Next to the shelves of assassination literature in the bookstore, a sign advertising a 50% off sale bears a Kennedy quotation: “Let us welcome controversial books and controversial authors”—their emphasis.) Half of the museum is devoted to explaining each of the five formal investigations and presenting each theory more or less neutrally. The Warren Commission concluded that Oswald acted alone, and the and the House Select Committee on the Assassination concluded that a conspiracy was involved. The museum labels are therefore written very carefully. One caption reads, “Oswald’s motive died with him in 1963. Most Americans believe he killed the President, or was involved in the assassination.” It’s not like they’re playing to a minority here. Most Americans have believed and continue to believe that there was some sort of conspiracy involved—as of 2013, according to the museum, 61%. The figure has been as high as 80%. So I don’t think they really had a choice here, but, given that difficulty, I’m not sure a museum was a great idea in the first place. Perhaps it’s more accurate to say that the museum’s not really about the assassination, but about everything that came after. Kennedy himself eventually recedes into the background.

VII. Repetition compulsion

The museum made me think about how often this sequence of events has been re-staged since November 22, 1963. The Secret Service re-enacted the events of the day on November 27 and again on December 5. The FBI conducted a re-enactment over two days in May 1964 for the Warren Commission’s investigation. In 1978, another forensic re-enactment was staged at the behest of the U.S. House of Representatives Assassinations Committee (this one was focused largely on acoustics). Then there are literally dozens (hundreds?) of TV shows and feature films and documentaries and novels. The repetition compulsion is remarkable.

Freud and his successors understood the repetition compulsion as an exercise in mastery: we manage grief and distress by reenacting the traumatic event. But Freud was struck by the fact that repetition seems to soothe, rather than inflame, distress. He asked, “How then does his repetition of this distressing experience as a game fit in with the pleasure principle?" Traumatic childhood events, Otto Feinchel subsequently wrote, "become sources of attraction," repeated in the hopes of mastering or resolving the experience. The implication here is that resolving the conflict relieves that compulsion. But what do we make of the fact that it seems to never end? I guess that’s what you call a fetish.

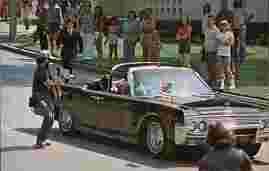

In 1975, two Bay Area art and design collectives, T.R. Uthco and the Ant Farm, went to Dallas to re-stage the Zapruder footage—not the event of the assassination, just the parts caught on film. All of this is documented in a film called The Eternal Frame.

There’s more to it, but I was particularly interested in the interactions between the artists and the people milling around them, tourists who had come to Dealey Plaza and stopped to watch. Many photographed and filmed the spectacle themselves. It seemed to them to be no different than witnessing the original event.

“Oh, no,” one woman says, when the Kennedy figure, called The Artist-President in the film, is shot again, and cries. “I’m really glad we’re here,” she says. “I really am. We made it just in time to see this. I feel bad and yet I feel good,” and she laughs. “Beautiful enactment. I wish I had a still camera … It was too beautiful.”

Another woman comments that Dealey Plaza doesn’t look the way she expected it to, it looks artificial, the man in drag is obviously not Jackie Kennedy. But after the re-enactment she says, “It looks so real now, the characters look so real.” What does that mean? It looks so real now.

After they’re done filming the re-enactment, The Artist-President and The Artist-Jackie, still in character, go across the street to the JFK Museum, home of The Incredible Hours, and sign some autographs for visitors; the manager asks them to leave.

My favorite part of the film is this ad lib interview with a guy in character as a secret service agent. “Unfortunately, we fucked up on this one,” he says. “What do you mean?” he’s asked. “Well, he got killed.” Not for the first time, or the last.

The Sixth Floor Museum, Dallas, TX: ✰✰ 2 stars (out of 4)

Psst, if you sign up for an annual subscription today, I’ll send you one of the few remaining print copies of Trying to Make the Personal Political: Feminism and Consciousness-Raising, which I published with Mariame Kaba in 2017, as my thanks.

According to Margaret and Sophie of Two Bossy Dames!

DHB was the cousin of polar explorer Robert Byrd, who named a mountain range after him. DHB’s son Caruth was a television producer whose Hollywood neighbor was Gene Autry.

Mayhew also wrote that classic of the genre, “Don’t Monkey with Another Monkey’s Monkey.” He is the author of the 1966 book The world's tribute to John F. Kennedy in medallic art: medals, coins and tokens--an illustrated standard reference. (Another writer published a book about the “medallic portraits” that year, too. How far down does this thing go? I couldn’t tell you.)

The Plaza finally became a National Historic Landmark in 1993.

The story of the first one is completely fucking bananas and trying to explain it will take me and this newsletter down.

Mr. Sissom, who ran the museum with his wife Estelle, was also a professional magician!

Did, uh, anyone ask the Kennedys what they wanted? Yes! They did not like it! Edward Kennedy said that his family found it "disturbing,” though they did not interfere in the project.

Two months later, another museum opened up about three blocks away. Admission was $3.99. Stay petty!!!!

My understanding is that visitors typically wear headphones and listen to audio tours and they are maybe not doing that during the COVID times, but I can only tell you about the place I saw.

I think this is extremely fucked up!!!

Oswald’s mother Marguerite also claimed to be a researcher and had an expansive library of assassination literature when a writer for Crawdaddy visited her in 1977. She only agreed to speak to him if he promised to pay her. "This is free enterprise. It's profit-sharing," she said. Here’s a rather chipper photo of Mrs. Oswald standing in front of the Book Depository in 1964.

Thanks for all this info. The Sixth Floor Museum kindly let me use images from the Zapruder film for my novel. But I've never spent time in the city, so I haven't visited. I'd like to.

You wrote “Though the Warren Commission and the House Select Committee on Assassinations both concluded that Oswald acted alone…” This is false. The HSCA concluded that President Kennedy “was probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy.” See the original document:

https://history-matters.com/archive/jfk/hsca/report/html/HSCA_Report_0063a.htm