Hooked on a feeling: Birthright Israel's affective politics

Or: You can't be neutral on a tour bus rolling toward the foot of Masada

My friend [redacted] sent me this text message on Monday, two days after Hamas militants launched a surprise attack on Israel from the Gaza Strip, the details of which you almost certainly already know. You likely know, too, that the Israeli military’s reprisal was accompanied by shutting off food, water, electricity, and fuel supplies; you may also know that Israel advised the Palestinian authority to evacuate 1.1 million people from North Gaza within 24 hours and that this increasingly looks like a prelude to genocide. You also know—maybe better, in fact, than anything you know about the actual events—a great deal about how American Jews have responded.1 I (an American Jew) responded by tweeting the screenshot with the caption “wow, Birthright works.”

That is basically all I’ve had to say in public about any of this. I just don’t know that much. I have thoughts, but that’s all they are. I feel like these thoughts are meaningful, and more than once I did consider saying more. But why does it feel like I have an informed position? Well, because I was taught that—not information, but that feelings of affinity with Israel constitute knowledge, expertise. I think this is true of a significant majority of American Jews—that these feelings, which we believe come from and are (somehow?) inextricable from our Jewishness constitute knowledge about Israel.2 They don’t. An erotic attachment doesn’t constitute knowledge about Israel or Gaza or the politics of the region.

But here’s the thing: we, American Jews, were taught that it might. This was a programmatic part of our communal religious lives, at the cost of hundreds of millions of dollars. The mobilization of those feelings now—the return, if you will, on that investment— contributes to a cacophony of recrimination that has very little to do with what is actually happening in Israel and in Gaza. How exactly that happened is something I know about, so I thought I’d tell you.

Since World War II, philanthropists have poured hundreds of millions of dollars for programming and education efforts implemented by the major denominations that has produced in American Jews an affective connection to Israel—and to Zionism—that mobilizes us in advance of politics and activates a political will that may or may not be entirely our own. One of the most successful of these programs has been Birthright Israel, a program that sends Jewish young adults (18-26) on completely free ten-day trips to Israel and the Golan Heights. The goal is simple:

Birthright Israel seeks to ensure a vibrant future for the Jewish people by strengthening Jewish identity, Jewish communities, and connection with Israel.

Launched in 1999, a year before he outbreak of the second intifada (expedient!), Taglit-Birthright Israel has sent more than 500,000 North American members of the Jewish diaspora on these “life-changing trip[s] to Israel.”3 Today, around forty-four percent of American Jews between 18-46 have been to Israel; of this group, a little less than half have been with Birthright. Twenty percent of American Jews between 18-46 have traveled to Israel with Taglit-Birthright Israel.4

Such trips aren’t exactly new—Zionist youth movements, American Jewish denominations, and the government of Israel have been bringing young diaspora Jews to Israel since the 1950s—but Birthright’s interest in reaching unaffiliated Jews is newer. For obvious reasons, trips organized by the Conservative movement’s United Synagogue Youth (USY) and the Reform movement’s National Federation of Temple Youth (NFTY) have focused on communally engaged Jews. Birthright boasts that all young Jewish adults are welcome on its tours.

Birthright tourism is also a little … softer than some other programs have been, which have traditionally included, for example, fairly intense physical activity and labor on communal farms called kibbutzim. Early Zionist nation-building among Israeli pioneers was effected in part through tiyulim, long, difficult communal hikes.5 Birthright definitely delivers “a barrage of physical and emotional highs.” The trips are designed around experiences that produce “uncommon or intense bodily solutions”: visiting open-air markets, moving among the crowds at the Western Wall, clubbing, riding donkeys, floating in the Dead Sea, and, yes, hooking up with one another and with Israelis.6 But the bus is air conditioned and you only sleep in a Bedouin tent for one night.

The trips are built on tightly-scheduled itineraries that keep travelers busy for 15 hours a day.7 Groups of 30 to 40 travel to the country with counselors, where they’re met by Israeli guides who lead the trips. They look fun! (I have never been to Israel.8) Key to the formula is cultural exchange with young Israelis, which Birthright calls mifgash, or “encounter,” which began in 2002. Between six and eight join each group for at least half of the trip. Typical makeup of the Israelis who participate: usually secular and of European descent; about 70% on active military duty (and therefore wearing uniforms); slightly more likely to be men than women.9

And the formula works. According to Birthright, alums are 85% more likely to feel “somewhat or very attached to Israel” than peers who have never been to the country. Fifteen to twenty years later they are 93% more likely to “be ‘very much’ connected to Israel than non-participants.”10 Some research suggests that their parents feel more connected to Israel, especially if they themselves haven’t been.11 Birthright travel is incredibly successful in strengthening participants’ emotional connections to Israel and Israeli Jews.12 In some ways, that’s not so surprising. Putting people through an intense, emotionally absorbing, and mildly physically taxing group experience produces strong feelings of affinity and connection, regardless of where it happens and with whom; such affective work is applied to all kinds of ends, good and bad. Birthright does it in Israel with Israeli Jews.

We might think of Birthright’s work as what scholar Shaul Kelner calls “diaspora-building,” though the organization does not use such language. Talk about closing the distance between Israel and diaspora communities, as Kelner explains, actually elides “the fact that the element of distance is the essential defining feature of the relationship.” Feeling about Israel from a distance, rather than thinking closely about Israel or, you know, moving there, is the point. And this works specifically because diasporic subjects (especially those from nominally multicultural societies) “reject the notion that citizenship alone should define the boundaries of political community.” Which, when you think about it, is weird, Kelner says: Zionist ideology traditionally “holds out immigration as the preferred path.”13 This is something else, a geopolitically expedient Zionism that affirms nation-building from afar—they’d like you to call your representatives, not move in. Israelis visiting the United States do not feel (or politically need to feel) such a connection.

It’s because Birthright claims that the program is not political that these feelings seem to be above suspicion. There’s now a two-hour lecture on geopolitics!14 Sure, you’re free to ask any question you want! Yes, your tour guide can speak candidly about the ideological elements of the conflict! They will answer your questions honestly! No one tells them what to say! But Birthright tells them where to go and with whom. Travelers don’t go to Arab sites or spend time in Arab communities or invite Israeli Arabs—much less Palestinians—to participate in mifgash. (And Jewish young adults, activists and non-activists, have been more critical of this in recent years.)

Explicit political rhetoric might be carefully constructed as neutral. But the program’s “political socialization,” as Kelner puts it, is not. “Even in the most balanced of scenarios.” he writes, “… when the discourse paints both Israelis and Arabs in shades of gray, the experience of Israel, and Israel alone, occurs in 3-D Technicolor with Surround Sound.” And that makes sense! The point is not to send Birthright participants home conversant in, or even much interested in, Zionist politics. It might be better if they aren’t! The point is that they feel fondly towards Israel and by extension its politics—that they have an image in mind when Israeli politicians talk about doing whatever is necessary to preserve the Jewish state.

The point is not to send Birthright participants home conversant in, or even much interested in, Zionist politics. It might be better if they aren’t!

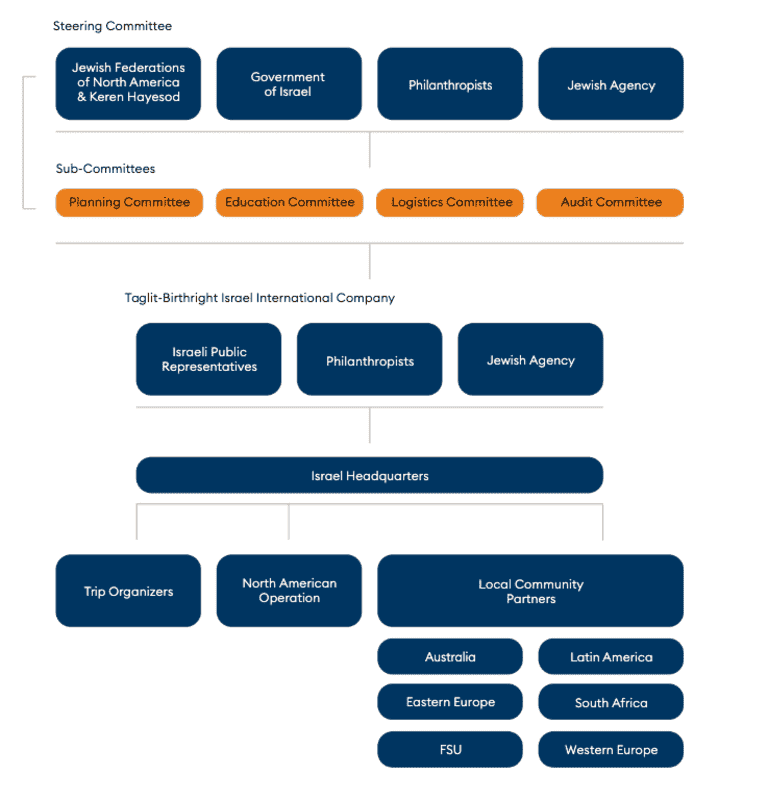

The Birthright program is the joint project of the State of Israel, American philanthropists, and, to a much smaller extent, Jewish communal NPOs. The “initial spark” came from an Israeli politician: Yossi Beilin, who was Deputy Foreign Minister when the Oslo Accords were brokered in 1993. Shortly after, Beilin told American Jews that “every young Jew [should] receive a birthday card from the local Federation on his or her seventeenth birthday with a coupon for travel and accommodations in Israel during the next summer vacation.”15

Just as the Oslo peace collapsed and new violence broke out (how expedient!), billionaire philanthropists Charles Bronfman and Michael Steinhardt took Beilin’s advice. Bronfman has led significant philanthropic efforts centered on Israeli-diaspora relations through his eponymous foundation since the 1980s. In the following decade, he convened a handful of millionaires and billionaires for his “Mega Group” and brought them to annual retreats to learn about Jewish history. Many of the resulting projects target children and young adults—funding for summer camps, day schools, university Hillels, and, yes, trips to Israel. Bronfman’s philanthropists, the Israeli government, and Jewish NPOs administer Birthright together:

The American community partners fill the bus, the Israeli government provides the soldiers, and Birthright pays for all of it.16 And all of these parties have an interest in producing the emotional results I’ve been describing.

All of this is to say is that [redacted]’s observation via text message checks out. We’re probably hearing from a lot of people who got laid on Birthright trips. The cultural exchange element of the program turns on17 the possibility. Birthright alums and program staff like to say that there’s way less hooking up on the trips than rumored, but … they’re talking about sex, not eroticism18. As Kelner put it, “the mifgash encounter is highly sexualized,” and specifically sexualized between Israeli men and American women. There is a lot of flirting, from all parties, and women on the tours can spend a lot of time competing with one another in ways that require literally no participation on the part of the men they like to think they’re pursuing. A young Israeli dude in fatigues is a great target for a little sexy Othering, and it’s not hard work for him. (And yeah, he can do some Othering of his own. I’m not saying it’s always one-way, just that the encounters can be eroticized without sex.)

The American Jewish communal apparatus has worked vigorously to tie feeling for Israel to Jewish identity and to persuade us that a Jewish state is the final bulwark against global anti-Semitism. That’s neither a secret nor in question. Another former Israeli statesman, Yossi Shain, has written that he sees “‘Israeliness’ as the current paradigm for world Jewry.”19 You would be forgiven for thinking that there is no way to be Jewish without Israel. That is not true. But the fact that it seems to be so is part of a larger story about the postwar diplomatic project of the Jewish state and the related, but not identical, post-Shoah project of invigorating Jewish culture and community. (Kelner calls this a “modern Jewish eschatology” expressed through “timeless biblical paradigms” of Jewish theology.20)

Aching for Israel is Birthright’s desired outcome. [Redacted]’s Insta friends, your friends, my friends—they may not believe the things they’re saying. They might not even know what they believe. They sure do feel it, though.

Our responses are diverse. I am not going to do backflips to demonstrate that or that I believe it. Demand that shibboleth from someone else.

Sometimes people have the feelings and the information, and if that’s you, cool. You can assume I’m not talking about you! But you probably know what I’m talking about.

Taglit-Birthright Israel CEO Report, 2021-2022, p. 17. Another 160,000 or so come from 65 other countries. Birthright gets to its 800,000 number by including 125,000 Israelis who have participated in mifgash. These figures about feeling tied to Israel are also the organization’s numbers. Other analysis suggests lower, though still significant, numbers. (There’s a TON of research on TBI conducted by researchers at Brandeis & information separately taken from Pew research on American Jews and I didn’t find numbers that high in what I browsed.)

“The Reach and Impact of Birthright Israel: What We Can Learn from Pew’s ‘Jewish Americans In 2020,’” Contemporary Jewry (2023)

Shaul Kelner discusss the tiyul at some length in Chapter 2 of his 2010 book Tours That Bind: Diaspora, Pilgrimage, and Israeli Birthright Tourism. (Nice review of the book here.) Israelis are perhaps constitutionally tough because their asses get dragged all over the country to Explore Nature in the name of nationalism. Your trip to the Grand Canyon could never. (West Bank settlers also use tiyulim to assert their occupation of land that isn’t theirs. Arguably that is partly what Americans do when we travel to national parks; that occupation is maybe a little less … fresh.)

Kelner, 134. He adds, “One key informant—who would later go on to rabbinic school, told me, “Everyone knows … that people hook up … and they sort of feel like they haven’t had a real Israeli experience until they have.”

Birthright itself funds the trips, but U.S. “provider groups” like college Hillels organize them, so some of the conformity is the product of the provider groups’ collective choices.

By the time I thought about a Birthright trip, I was already pretty engaged in a Jewish community—a queer community, to boot—and had come to feel pretty strongly about Judaism as fundamentally diasporic and non-Zionist. I don’t know, I was a little too old to see the whole thing as uncomplicated. I would have probably tried to extend the free airline ticket, which Birthright encourages, to go on a Birthright Unplugged trip, which they did not encourage and in fact punished by barring you from the trip if they found out in advance,

“Guest Host Encounters in Diaspora Tourism: The Taglit-Birthright Mifgash Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education,” p. 8

The Reach and Impact of Birthright Israel 2023, birthrightisrael.foundation.

“Reach and Impact: What We Can Learn,” 325. This one is crazy to me!!!!

There is also a robust effect on some aspects of secular Jewish identity. That’s important! It’s a problem, however, that throughout the Jewish communal world, the former is thought to be the best way to achieve the latter.

Kelner, xx & 34

“Birthright Trips, a Rite of Passage for Many Jews, Are Now a Target of Protests,“ New York Times, June 11, 2019

Qtd. in Kelner, 41

The Israeli government and Jewish NPOs do also pay for some of it. This is poetic license, LOOK IT UP. But some mifgash participants join because they have been nominated by their commanders (“Guest Host Encounters,” 8). And they often feel “very strongly” (78% in a 2007 survey!) that Birthright “strengthened the importance of their military service,” which seems great for cohesion.

See what I did there? 😈😈😈😈

The group’s FAQ response to the question “What’s the policy regarding sexual conduct on Birthright Israel?” is “We have a zero-tolerance policy towards harassment of any kind and promote a communal space of physical and emotional safety.” LOL.

“What We Can Learn,” 337

Kelner, xix

Thanks for this piece, J.

I had never heard of the Birthright program before today, so thanks for the illuminatination.